In Bolivia, Morales’s Indigenous Base Backtracks on Support

December 8, 2018 - NY Times

By Nicholas Casey

CARMEN DEL EMERO, Bolivia — In this remote indigenous village in Bolivia, the rule has been the same for generations: Leaders can be re-elected only once. After that, they must hand power to someone else. So it came as a shock to Nelo Yarari, the leader of Carmen del Emero, a community of indigenous Tacana people in the Bolivian Amazon, when President Evo Morales said he would be running for a fourth term. Bolivia’s Constitution barred him from doing so, and Mr. Morales lost a referendum two years ago that would have allowed him to run again. Instead of giving up, he leaned on the courts, which then threw out the country’s term limits. for Mr. Yarari: As Bolivia’s first indigenous leader, Mr. Morales had vowed to champion native values from the presidential palace.

In seeking for yet another term, Mr. Morales was violating a basic tenet of the Tacanas, power sharing. He was also pushing for oil and gas extraction in protected areas and proposing hydroelectric dams that would displace native communities.

“We don’t consider him indigenous here,” Mr. Yarari said. “He has turned his back on us.” With the election set for next year, the issue of a boundless presidency has become a broader concern for a Latin America where threats to democracy are mounting.

In Venezuela, President Nicolás Maduro now rules as an autocrat, extending his own term this year in an election widely seen as rigged. More than 300 people in Nicaragua have been killed in protests to end President Daniel Ortega’s tenure.

And some see an autocratic streak in Mr. Morales’s support for crackdowns by Mr. Maduro and Mr. Ortega and in his own history of attacking the media and stacking the courts with judges who favor him.

“Evo is now asking: What can I do to stay in power?” said Marcelo Arequipa, a political-science professor at the Catholic University of Bolivia in La Paz. “This issue has become so important it sometimes means sidestepping the Constitution.”

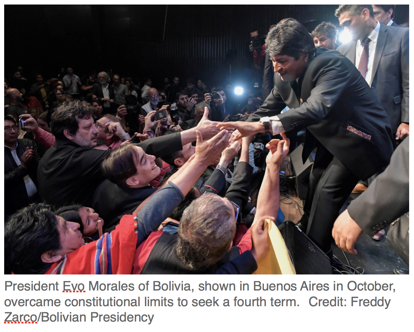

Mr. Morales, the former leader of a coca-growers union, was first elected in 2005 with broad support from the country’s indigenous majority, and reoriented policies in a way not seen since Bolivia was conquered by the Spanish. He called for the Constitution to be rewritten, promised to roll back centuries of racism and eschewed Western suits for attire using indigenous designs.

At first, many in Carmen del Emero — a two-day journey by river from the town of Rurrenabaque and more than 250 miles north of the capital — saw Mr. Morales as the antithesis to a long chain of leaders who did not represent their interests.

His predecessor, Gonzálo Sánchez de Lozada — known as El Gringo because he was raised in the United States and spoke Spanish with an American accent — proposed a tax plan that would have raised taxes on the poor, and presided over the killing of indigenous Aymara protesters before fleeing into exile in Washington in 2003.

Mr. Morales promised something different. He preached inclusion of indigenous groups, cut ties to American coca-eradication programs that stung farmers and used the state’s wealth to cut the poverty rate in half by 2012.

Yet 12 years after he took office, many indigenous groups are questioning whether it is their interests — or Mr. Morales’s own political ambitions — that are behind his unrelenting grip on the presidency.

The Uru, a fishing people on the Bolivian plateau, watched their lake and livelihood vanish under Mr. Morales’s watch because of climate change and the government’s diversion of water to subsidize large farms.

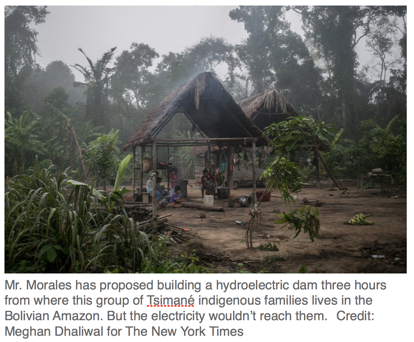

The Tacanas have sparred for years with Mr. Morales, who dusted off a previous government’s plan to build a hydroelectric dam near Madidi National Park, an area many of the group call home.

“We’ll be the first who get displaced by this,” said Felcin Cartagena, a resident of San Miguel, downstream from the site of the dam.

The president has even been abandoned by some indigenous coca growers, his early base. In October, a coca growers’ union from the Yungas region endorsed former President Carlos Mesa, Mr. Morales’s main rival in the race, after one of the union’s leaders was arrested on charges of planning an ambush that killed a soldier. The group said Mr. Morales was trying to quash the union by falsely accusing its leader.

Mr. Morales has done much to ensure he remains in office, including calling a constitutional assembly during his first term that allowed him to run two more times and pushing the referendum in 2016 that would have allowed him to run for a fourth term.

After that narrowly failed, the Constitutional Court, which is largely loyal to Mr. Morales, ruled last year that the president could run again on the grounds that term limits amounted to a human rights violation.

Adriana Salvatierra, a lawmaker from Mr. Morales’s party, Movement for Socialism, said the president had neither violated the Constitution nor lost support among native groups. His presidency empowers them by showing “the indigenous peasant as a revolutionary power,” she said.

Ultimately, she said, Mr. Morales needs to stay in power to counter ascendant conservative leaders in neighboring Brazil and Chile who she said were seeking to erase gains made by the poor.

“Evo Morales is the only one that can guarantee economic growth, stability, sources of work,” she said.

Indeed, Mr. Morales has delivered on many of those fronts, keeping Bolivia’s economy afloat even as Brazil and other nations in the region suffered through a recession when commodity prices slumped. But that is not enough, even for many of Mr. Morales’s erstwhile supporters.

“We have a president violating the Constitution — whether he’s done good or bad, it’s the Constitution,” Mr. Yarari, the leader of Carmen del Emero, said.

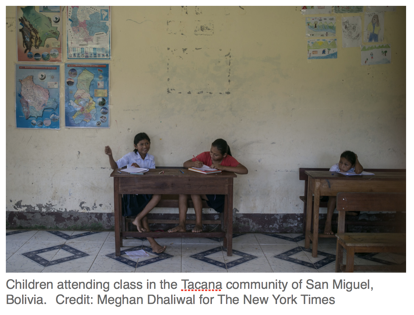

The Tacanas greeted Mr. Morales’s first election as their own victory and as evidence that, at last, the national government would begin to have a presence in the distant village, he said. Before long the government began collecting taxes from Carmen del Emero, charging the Tacanas for the caiman crocodiles they hunt and the timber they harvest.

But government services did not follow. The village school was built 40 years ago, the health center is 30 years old, and neither has been maintained, Mr. Yarari said. When floodwaters decimated the village in 2014, covering it in mud for months, it was the Red Cross that came to help, the leader said.

Further upstream along the Beni River is San Miguel, which is fighting Mr. Morales over the proposed hydroelectric dams. If built, the dams would flood regions around Madidi National Park in Bolivia’s northwest, considered one of the world’s biodiversity hot spots.

The Tacanas had spent years fighting previous governments over the project, but they were taken aback when Mr. Morales began pushing for it. In June, the indigenous group sent a small armada of canoes upstream to block the river, in an effort to keep engineers from the site.

The dam project would aim to supply electricity to Brazil, but not to Amazonian villages in the area, like San Luis Grande. That angered Triniti Tayo Cori, a leader of the Tsimané people.

“Through our own effort we’ve gotten light to our town: We bought a generator, we bought cables, we bought light bulbs,” Mr. Tayo Cori said, describing a recent effort to install public lighting after years of asking the government to do so.

Yerko Ilijic, a Bolivian lawyer and political scientist, said Mr. Morales was making his calculations based on votes: Small groups like the Tacanas and Tsimané aren’t a priority.

“When you’re a politician, who do you negotiate with?” Mr. Ilijic asked. “You negotiate with whoever has the biggest numbers.”

Mr. Ilijic said Mr. Morales appeared to be striking up alliances with some of the very landed interests he once fought. In September, he signed a law to use bioethanol as an additive in Bolivian gasoline, which was seen as a boon for the sugar industry. The farms that produce bioethanol have long angered indigenous groups for advancing deforestation.

For some, next month’s election will present a difficult choice between two unsatisfactory candidates: Mr. Morales and Mr. Mesa, who was vice president under Mr. Sánchez de Lozada, the exiled president who oversaw the Aymara killings that lifted Mr. Morales to power.

Rodrigo Quinallata, an activist in the city of El Alto, near La Paz, campaigned against allowing Mr. Morales more terms. An Aymara, he says he will continue that struggle.

“We have to admit that in the end someone who is wearing a poncho can be as corrupt as someone who is wearing a tie,” he said.

Correction: December 11, 2018

An earlier version of this article misstated an action on tax policy taken by Gonzálo Sánchez de Lozada as president of Bolivia. He proposed a tax increase that would have raised taxes on the poor; he did not raise taxes on the poor.