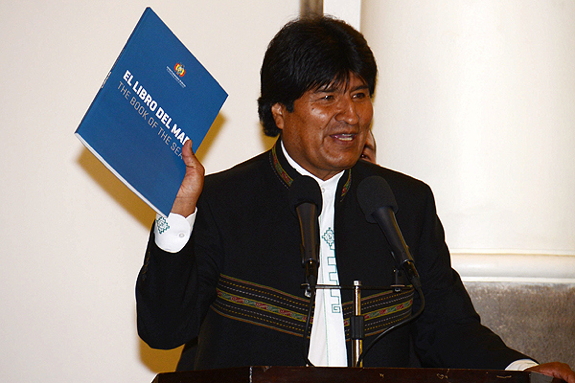

(above) Photo: EFE

Bolivia to Incorporate "Book of the Sea" in Public Education

March 26, 2015 - inserba.info

LA PAZ, Bolivia – At a recent commemoration of the loss of coastline to Chile well over 100 years ago, Bolivian leader Evo Morales announced that the "Book of the Sea," which explains the national cause of recuperating that coastline, will be included as one of the required readings in the public school system.

The book was written in 2014 by a team of historians and jurists led by former President Carlos Mesa (2003-2005). Mesa also heads the National Bureau of the Maritime Claim, a governmental group tasked with articulating the Bolivian perspective concerning the coastline before international forums and summits in the region and across the globe.

The group also includes Morales, Foreign Minister David Choquehuanca and former President and current Ambassador to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) Eduardo Rodríguez Veltzé.

The "Book of the Sea," written in Spanish and English, was first made public when it was given by Morales to all the attendees present at the G77+China Summit held in the Bolivian city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra in June of 2014.

The book and a subsequent video are broken down into segments that explain the Bolivian position on the case, segments like "History of the Bolivian Littoral Loss," "Chile's Commitment to Negotiate With Bolivia Over Sovereign Access to the Sea," "the Maritime Claim at the ICJ" and "the Consequences of the Confinement of Bolivia."

The references to the ICJ stem from the case filed by the Bolivian government at said legal institution against Chile in April of 2013 with an eye to eventually recovering at least part of the land lost to their neighbors during the War of the Pacific (1879-1883).

During that conflict, Bolivia and Peru were defeated by the invading Chile who annexed Antofagasta, Bolivia's only port and point-of-access to the sea (mentioned in the song), along with 420 kilometers (260 miles) of coastline. Additionally, Chile annexed over 120,000 square kilometers (46,000 square miles) of the Bolivian littoral, some of the most mineral-rich lands found anywhere on the globe.

The Bolivian argument states that Chile promised Bolivia a route to the Pacific through direct negotiations between the two nations in the 1970s when both nations were led by a military dictatorship but never fulfilled that promise. Chile, meanwhile, stands by the 1904 Treaty that was signed by Peru and Bolivia under disadvantageous circumstances that determined the boundaries which are still in place today.

The "Book of the Sea" explains the Bolivian standpoint and as such, Morales decided to incorporate it into the public education curriculum: "It has been decided that the "Book of the Sea" will be an official work used in the public education system and it will be compulsory," he said.

The act was dripping in patriotic and nationalistic sentiment as Morales made the announcement in La Paz's Plaza Abaroa, a city square named after Eduardo Abaroa Hidalgo (and adorned by a bronze likeness), the man considered a national hero in Bolivia for his bravery. Abaroa Hidalgo led a civilian regiment that was outnumbered and underequipped and when much of them withdrew, the man who would become legendary stayed on his own and fought to his last breath and refused to surrender.

The sights of the square and marching troupes of military, police, students, indigenous and other organizations were matched by sounds on March 23, a national holiday in Bolivia that commemorates Abaroa's death in 1879, as the "Hymn to the Litoral" played in the background.

The Hymn, a patriotic song that promises to recoup the territory lost, is played at all official acts of the government, including those attended by Chilean delegates which sparked anger in Chile as their representatives listened to the song while attending the January swearing-in ceremony for Morales' third consecutive presidential term.

The ceremony, marked by indigenous Aymara music, art and traditional rites, was capped by a singing of the song which is very loosely translated as follows: "We sing the song of the sea, the sea, the sea, that will soon be ours again, let us raise our voice in happiness for the Litoral that Bolivia will soon have again, its sea, its sea, Antofagasta, beautiful lands of Tocopillo and Mejillones next to the sea, with Cobija and Calama, return to Bolivia again."

The song's lyrics were written by Gastón Velasco while the music was composed by Eduardo Otero de la Vega in 1979, the centenary of the territorial loss suffered by Bolivia after it was invaded by Chile.

In 2011, Morales signed a decree that the song would be used in all official acts of the Bolivian State to show how much importance his administration had placed on the recuperation of the territory. Since then, other acts, with the most recent being the introduction of the "Book of the Sea" in the public education system, have served to shed light on the Bolivian desire for sovereignty to the sea.

"This book is just part of the obligation of all of our Bolivian compatriots to keep alive the patriotic memory of the significance of the Chilean invasion, the significance of sovereign access to the sea, and this must be passed onto our children," Morales said.

In July of 2014, Chile decided to challenge the jurisdiction of the ICJ, thereby contesting the power of the Hague-based court in hearing the case and handing down an enforceable decision. The decision, according to Santiago, was made after current politicians and prominent national figures consulted with former leaders and political figures of all political orientations.

If it is interpreted that Bolivia is simply attacking the 1904 treaty, the ICJ's jurisdiction will be nullified in determining the disagreement, and that is exactly what Chile wants. Thus, the Foreign Ministry of Chile said that it will be including this latest case of "provocation" when the first oral arguments of the case are heard in early May.

"Displays like this show exactly what is behind Bolivia's case, which is nothing but a broad claim of territory," argued the Ministry. "These things are just more evidence for our side against this misled claim," Chile argues, referring to the song's performance and the textbook development.

Morales has qualified Chile's decision to challenge the ICJ's competence as "arrogant" and "pretentious." The decision was "contradictory" because "Chile declares itself a nation that respects international law and treaties and yet simultaneously, it rejects the principal organ that administrates justice in international affairs to resolve disputes between States," Morales said.

Chile is a signee, as is Bolivia, to the American Treaty on Pacific Settlement, known as the Pact of Bogotá, which established in 1948 that signees to the pact would settle disputes through exhaustive peaceful avenues and if this did not produce a result, they were to then defer the definitive ruling to the ICJ. Chile says this does not matter, however, as the Pact of Bogotá does not grant the ICJ jurisdiction to preside over cases or situations that occurred prior to the Pact's establishment in 1948. Accordingly, the Court has no jurisdiction in this case, according to Santiago.

For Morales, however, the ICJ is the "only institution competent enough to resolve this case" because of its dependence on the "findings of fact and international law which were reflected in the case" filed by Bolivia.

"Bolivia is, as I have said before, a pacifist country and our only weapons are the rights, laws and reason. It is in this confidence that we assure everyone that we will continue working with the same dedication and accountability to defend our case," Morales said.

"It is certainly better to be involved in issues like this through a legal right and not through an unjust invasion of another country, and that is something that some Chilean figures that disagree with the case should know," Morales said in a poke at his neighbors to the west.