(above) The worst drought in almost a century has hit São Paulo, where this vendor sells water bottles to offices. Photograph by Nacho Doce, Reuters

Quirky Winds Fuel Brazil's Devastating Drought, Amazon's Flooding

February 26, 2015 - News National Geographic

Boom-and-bust water phenomenon could become a new normal in South America, scientists say.

Barbara Fraser for National Geographic

In São Paulo, Brazil, which is suffering its worst drought in almost a century, Maria de Fátima dos Santos has lived for days at a time with no water, relying on what she had carefully hoarded in bottles.

But in the Bolivian Amazon, about 1,800 miles (2,897 kilometers) away, Nicolás Cartagena recalls the day almost a year ago when floodwaters rose to the thatched rooftops of Indian communities, destroying crops and washing away homes.

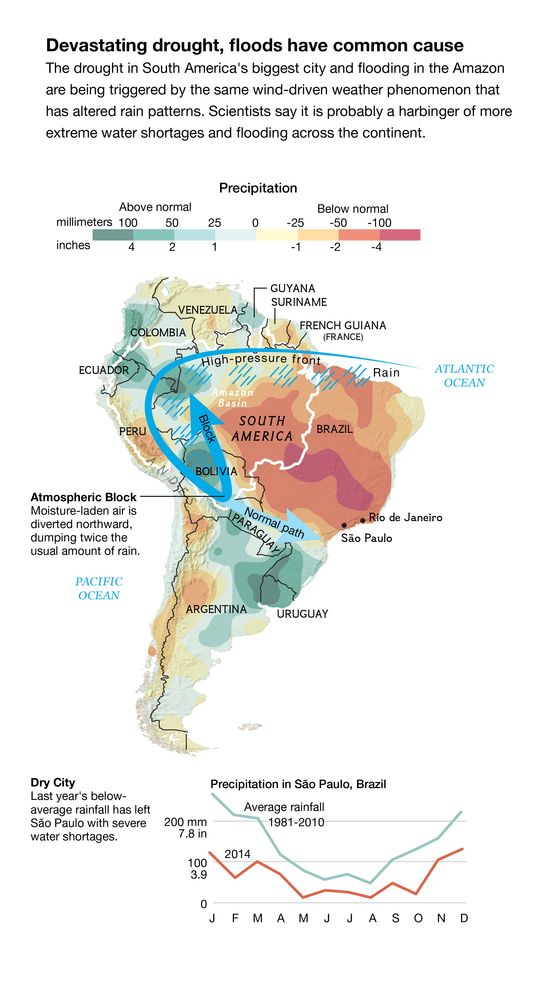

The drought in South America's biggest city and the flooding in the Amazon are being triggered by the same wind-driven weather phenomenon that scientists say is probably a harbinger for more extreme water shortages and flooding across the continent.

No one fully understands this boom-and-bust cycle, but meteorologist José Marengo says it has been triggered by a sprawling high-pressure system that settled stubbornly over southeastern Brazil. That region is usually at the end of a long loop of moisture-bearing trade winds. Last year, however, this system went awry.

(below) VIRGINIA W. MASON, NG STAFF; MAIA WACHTEL SOURCE: INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE PESQUISAS ESPACAIS

The loop starts in the Atlantic Ocean, where the winds carry moisture westward over the Amazon. Some falls as rain, but as the air passes, it also absorbs moisture from trees. When these "flying rivers" hit the Andes, they swing south, showering rain over crops and cities in eastern Bolivia and southeastern Brazil.

Beginning a year ago, however, a phenomenon called "atmospheric blocking" transformed that wind pattern. Marengo, a senior scientist at the Brazilian National Center for Early Warning and Monitoring of Natural Disasters (CEMADEN), likens this to a giant bubble that deflected the moisture-laden air, which instead dumped about twice the usual amount of rain over the state of Acre, in western Brazil, and the Bolivian Amazon, where Cartagena lives.

At the same time, cold fronts from the south, which cause precipitation over São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, were shunted aside, and as the system lingered, the drought took hold, Marengo said in an interview.

Such prolonged events may be unusual, but they are not unheard of.

(below) This aerial view of the Atibainha Dam, part of the main reservoir system that supplies São Paulo, shows the severity of the drought. The water level is at 6 percent of its capacity, a record low. Photograph by Victor Moriyama, Getty

A similar phenomenon five years ago led to devastating floods in Pakistan that killed at least 1,700 people and a scorching heat wave and wildfires in Russia that killed an estimated 15,000. More recently, California's drought was triggered by a similar high-pressure system that developed in 2011 and has persisted, with help from weather patterns in the Pacific Ocean.

Scientists aren't sure what caused the atmospheric blocking to linger over southeastern Brazil. Although this episode of flooding and drought is attributed to an isolated weather pattern, rather than climate change, "it could be a sign of what lies ahead if temperatures continue to rise as projected," Marengo said.

Constant Boom and Bust

People living along the Amazon and its tributaries have adapted to a constant aquatic boom and bust, with water rising as much as 30 or 40 feet (9 to 12 meters) to lap at the floorboards of their stilt-raised houses early in a typical year, and then receding every May or June until the rains begin again toward the end of the year.

That cycle becomes more dramatic when various natural forces—such as El Niño and altered sea-surface temperatures—combine to trigger severe drought and flooding.

Scientists in the Amazon say human activities, such as large-scale deforestation, could be exacerbating these wild swings in moisture, making them more frequent and extreme.

"To the extent that humans are altering the landscape and making droughts worse, it can affect the whole region," said Michael Coe, a senior scientist and leader of the Amazon program at the Woods Hole Research Center in Massachusetts, who studies land-use change and water cycles in Brazil.

(below) Thatched-roof homes in the Bolivian Amazon were flooded by the Beni River a year ago. More than 50 people died and about 150,000 lost their homes or property. Photograph by Aizar Raldes, AFP/Getty

Clearing forests raises temperatures locally and dries out the edges, making them more likely to burn. With heavy rains, runoff from deforested areas increases the hazard of flash flooding or landslides that destroy roads and bury homes. Runoff can also choke a river with sediment, narrowing the channel and making it more prone to flooding.

Dams built to generate electricity in the Amazon also can increase flooding. Last year's heavy rains in western Brazil inundated a section of a highway, cutting Rio Branco off from the rest of the country. That flooding was aggravated by dams on the Madeira River, said Philip Fearnside, research professor at Brazil's National Institute for Research in the Amazon in Manaus.

In Bolivia, the Beni River rose suddenly, swamping houses and cassava crops in Tacana Indian communities. More than 50 people died along Bolivia's Amazonian waterways and more than 150,000 people lost homes, animals, and other property.

"We went hungry, because we couldn't work and families had no money," Cartagena recalls.

Brazil's Biggest City Dries Up

Meanwhile, in São Paulo, the drought has nearly depleted the biggest reservoir in this city, the bustling economic center of Brazil.

The water shortages have been building for a year, and critics say the government was slow to respond. In an open letter last November, the Brazilian Academy of Sciences called for a "drastic reduction in water consumption" in 2015 as well as improved water system management and construction of new storage systems.

Brazilian officials say they now are considering rationing—although for São Paulo residents, the low pressure and interrupted water service already amount to that.

"We can't buy or store enough water to wash the dishes," dos Santos says.

"Buying paper plates isn't a good solution either," neighbor Francisca Sirlene da Costa adds. "If everyone in São Paulo just used one paper plate a day, it would be very bad for the environment."

A storage tank on da Costa's roof keeps the tap flowing when city water does not reach her neighborhood. But she worries that water from the dregs of depleted reservoirs may be polluted.

(below) A demonstrator holds an upturned umbrella before a cordon of police during a protest of water rationing in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Photograph by Andre Penner, AP

The timing of this crisis couldn't be much worse: It hits just as Brazil is preparing to put on a show for the entire world with the 2016 Summer Olympics.

Meanwhile, the weather system that scorched São Paulo has dissipated. Rain fell there and in Rio during the recent Carnival celebrations, and more is likely in weeks ahead.

That's the good news. The bad news is that the rainy season usually ends in April, so many more dry months lie ahead that will shrink the water supplies even more.

"It's like a seriously ill patient who is now a little less seriously ill," Marengo said.

Catherine Heinhold contributed to this story from São Paulo.