The 'Catholic witchdoctors' of Bolivia: Where God and ancient spirits collide

September 17, 2014 - CNN

By Jake Wallis Simons, for CNN

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

• A new book records the extraordinary world of Bolivian spirituality

• Catholic deities are seamlessly incorporated alongside local spirits

• The Aymara people live simultaneously in modern and traditional societies

• Every aspect of life is determined by ancient rituals

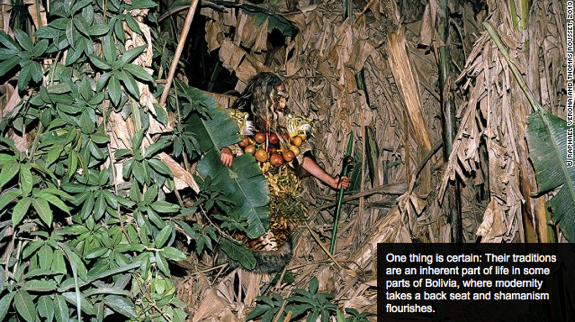

(CNN) -- On the vast plains of the Altiplano plateau in South America live people who believe in magic.

Many of the Aymara -- an ancient, indigenous race found in Bolivia, Peru and Chile -- suppose that on Tuesdays and Fridays, ordinary people become vulnerable to harmful spirits and the evil eye.

That's why on those days they stay awake and on their guard until dawn. And that is why they get together and smoke.

2

"When you exhale the smoke, you send back the evil spells to the sender," says Raphaël Verona, a Swiss photographer who has just released a new book of photographs of traditional Aymara communities.

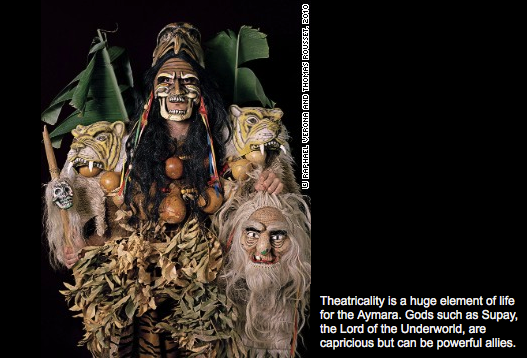

"You must also constantly pay homage to the spirits. There is a great variety of different spirits, such as the earth mother Pachamama, Supay, the god of the underworld, and the Virgin Mary."

Earth Mother; God of the Underworld; and the Virgin Mary. From the point of view of the Aymara, there isn't an odd one out.

A blend of animism and Catholicism

Catholicism first arrived in the region with the Spanish colonialists in the 16th Century. The early missionaries tried to encourage indigenous people to accept the Catholic God by reinterpreting their own spirits: Pachamama, they said, was Mary, and Supai was the devil.

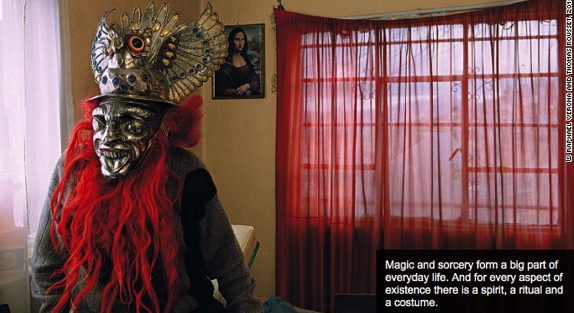

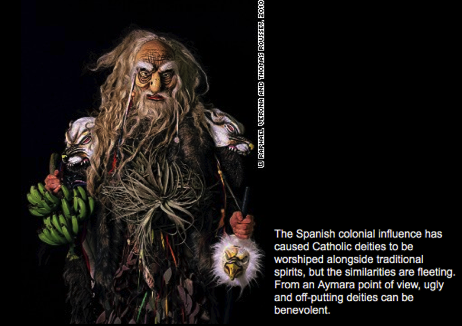

But the match was largely erroneous. Unlike the Catholic gods, the indigenous spirits were not seen as wholly good nor wholly bad. They were believed to be capricious yet compassionate; though they could cause calamities when slighted, they could be powerful allies when appeased.

Moreover, from the point of view of the Aymara, the terrifying appearance of spirits like Supai, who is depicted with horns and a scarlet face, did not simply signify evil. Rather, it was a reflection of power, which could be used for good or ill.

Because of these irreconcilable cultural differences (which the missionaries had failed to appreciate), Catholic gods were simply added into the Aymara pantheon. Christian rituals became blended with traditional beliefs, adding another dimension to this colorful, hybrid faith.

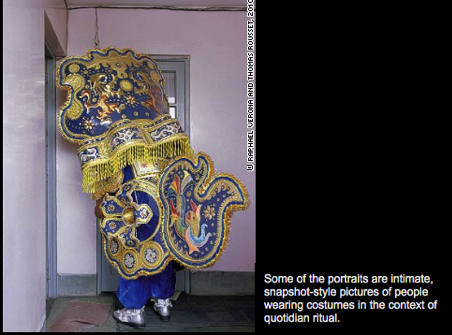

Elaborate traditional ceremonies such as Tinku and the Oruo carnival, which involve costumes, dancing and singing, are still practiced as they have been since time immemorial. But Catholic saints are included alongside the local deities.

The paradox of the Aymara

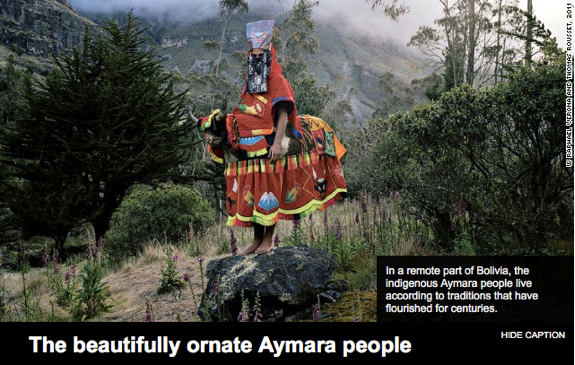

"The Aymara people have an approach to life that seems paradoxical from the outside," says Verona. "In Europe you are either one religion or another, either traditional or modern.

"But in Bolivia people live with both Catholicism and animism, both in modernity and in their ancestral traditions.

"They visit the Yatiri, the priest, to pay homage to deities or give prophesies when they are applying for visas, or for assistance in businesses matters."

Despite their acceptance of modernity, the Aymara also have little truck with the idea that the spirits might not be literally real.

"Traditional stories are seen to be as true as the people talking to you at this moment," Verona explains.

"If you ask someone if Supai, the god of the mines and the underworld, lives, they will say of course because they heard stories about it. So myths come to life very strongly in this society."

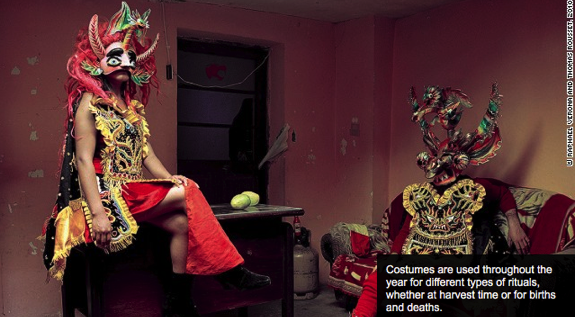

Verona first encountered the Aymara when he was living in Bolivia four years ago. There he met his wife-to-be, who is from the Aymara community, and began to meet her family and wider circle.

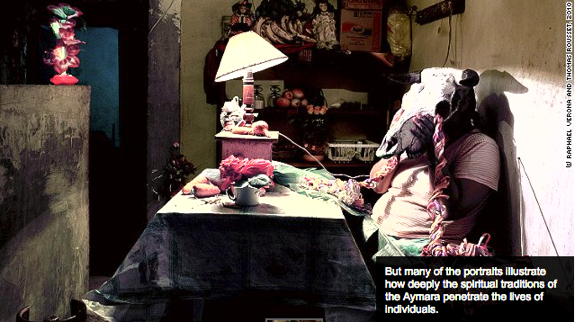

"I found myself entering an alien and beautiful culture," he says. "My parents-in-law would regularly carry out rituals involving offerings of cocoa leaves, alcohol, threads of dyed wool, sugar, and molded figures to the spirits."

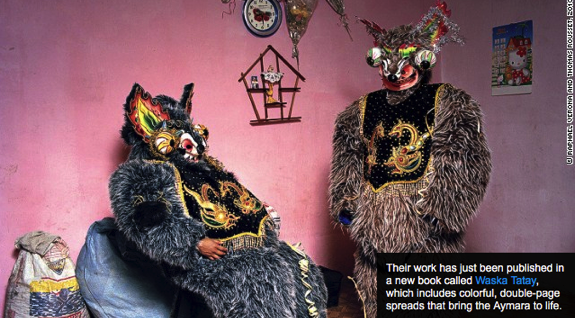

It was the costumes that particularly impressed him. Enchanted by the striking masks and outfits worn by shamans and dancers, he headed back to Switzerland and convinced his friend, the photographer Thomas Rousset, to collaborate in a photography project.

Many of the portraits were staged in people's homes, offering a contrived, theatre-like effect; others were taken as "snapshots". Together, this collection offers a potent evocation of this unusual and thought-provoking way of life.

"It is extraordinary to see this rich native tradition that challenges Western thinking," Verona says. "I think there is much we can learn from them."