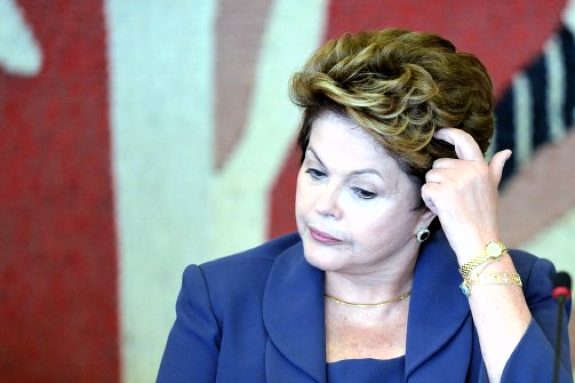

(above) Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff attends a ceremony commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Social Development Council at Itamaraty Palace in Brasilia on July 17, 2013. (Evaristo Sa/AFP via Getty)

Escape from Bolivia

September 2, 2013 - The Daily Beast

by Mac Margolis

A prominent critic of Bolivia's president has dashed from an embassy in La Paz to Brazil, where he has asylum. Mac Margolis on the ensuing diplomatic crisis.

With prices rising, the economy flat, and angry citizens ready to march at a moment's notice, Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff has plenty of worries. The only thing missing from Latin America's busiest inbox was a full-blown diplomatic crisis. Thanks to a clandestine border crossing by a political refugee, a testy leader in the Andes, and a bad case of foreign policy drift, now she has that, too.

Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff attends a ceremony commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Social Development Council at Itamaraty Palace in Brasilia on July 17, 2013. (Evaristo Sa/AFP via Getty)

The crisis blew up over the weekend when Bolivian Senator Roger Pinto Molina, a fierce critic of President Evo Morales, slipped out of the Brazilian embassy in La Paz, where he had been confined for more than a year, and made a 1,000-mile dash to freedom over the border. Molina's arrival, on Saturday morning, took Brasilia by surprise. And if there's one thing the protocol-bound Rousseff hates, it's going off-script. Suddenly, the switchboard at the Planalto Presidential Palace was ablaze as La Paz demanded explanations and the Latin American press corps clamored for details about the brazen Andean escape. By Monday, Brazil's Foreign Minister Antonio Patriota was out of a job, the opposition cheered, and Rousseff was trying to paper over a continent-sized political mess.

Merely taking in a refugee might not have triggered an international incident. Latin America has a long tradition of honoring appeals by political undesirables from neighbors near and far. The Bolivian lawmaker had won diplomatic asylum in Brazil over a year ago, and by the 59-year-old Caracas Convention, to which La Paz is a signatory, he ought to have been cleared for safe passage months ago. But in a region where playing to the gallery often trumps the rule of law, a treaty is only as good as the whim of the presiding supremo.

As it happens, Pinto Molina is the leader of the Bolivian opposition front and has been a stone in Morales' shoe almost since 2008. For the past five years, he has openly criticized the Morales government, calling out the ruling Movement Towards Socialism party for its open support of Bolivian coca growers and their shadowy links to drug traffickers who control a large swath of the country. Morales, who keeps a close watch over the judiciary, struck back with repeated lawsuits, charging Pinto with crimes from slander to corruption. When legal threats turned to death threats, Pinto fled to the Brazilian embassy and 11 days later, in June 2012, won diplomatic asylum.

Still, Morales refused to grant him safe conduct on grounds that Pinto stood accused of common crimes. "We have no political persecution here," said Bolivia's communications minister, Amanda Dávila. Facing four arrest warrants and sentenced in absentia to a year in jail for one of the 20 charges he faced, Pinto was stuck in a 4-by-5 room at the Brazilian embassy, pacing the floor, listening to Frank Sinatra, and taking in sunlight through a window pane. The impasse was broken last Saturday when, after 455 days of confinement, a consular deputy secreted the lawmaker out of the embassy to a waiting diplomatic car and drove down the spine of the Andes to the Brazilian border.

After 455 days of confinement, a consular deputy secreted the lawmaker out of the embassy to a waiting diplomatic car and drove down the spine of the Andes to the Brazilian border.

The escape was cinematic. The Bolivian lawmaker was accompanied by Brazil's business affairs attache, Eduardo Saboia, and two Brazilian marines assigned to the embassy. Some Brazilian media suggested that three Brazilian federal police agents also were part of the two-car convoy. Leaving La Paz in the early morning, the two cars wound their way through ice and snow atop 15,000-foot peaks to the steamy tropical lowlands of the Chapare, the heart of coca growing country. "The area is totally controlled by coca farmers loyal to Morales. If we were found out, it could have meant sure arrest or even death," said one member of the convoy, who asked not to be identified.

Though details of the 22-hour ordeal are still murky, the embassy vehicles apparently were stopped five times at police roadblocks. At one, Bolivian authorities not only inspected the vehicles—a routine in drug country—but also asked that all passengers step out of the cars, which Saboia promptly refused, claiming diplomatic immunity. Luckily, no one demanded that Pinto show his identification (fueling speculation that La Paz had unofficially consented to the escape).

In an isolated patch of lowlands, near the Brazilian border, the convoy stalled, apparently for lack of fuel. That's when Pinto Molina, an ordained Baptist reverend, and Saboia, a Roman Catholic, got out of the car and prayed. They returned to the vehicles, and surprisingly, both engines turned over allowing them to reach the Brazilian border town of Corumba. "It was the miracle of the multiplication of gasoline," Saboia later told a Bolivian reporter.

Bolivian and Brazilian officialdom were not amused. Bolivian Foreign Minister David Choquehuanca expressed "deep concern" over the "assisted flight" of Pinto, which he termed "a transgression of the principle of reciprocity and international courtesy."

Rousseff, who learned of the incident only after Pinto Molina was on Brazilian soil, publicly reprimanded her diplomatic corps, without citing either Saboia or Patriota by name. "I deeply regret that someone granted asylum by Brazil was exposed to such danger," she told reporters in Brasilia. Known for her short fuse, she reportedly pounded her desk in a closed-door meeting with Patriota and asked for the foreign minister's resignation on the spot.

Sources close to Brazil's foreign service say she was especially annoyed over the foreign minister's efforts to downplay the incident as well as by Saboia's attempt to justify his actions by comparing Pinto Molina's "inhuman" confinement to Rousseff's own experience as a political prisoner during the Brazilian dictatorship. "I know what it was like," she said of the military junta's dungeons. "I can assure you that it's as different from the Brazilian Embassy in La Paz as heaven is from hell."

But more than rogue diplomacy was on display in the Andean escape. Long respected for its professional diplomatic corps dedicated to defending human rights and international justice, Brazil is better known today for caving in to the ideologically inflated agenda of the so-called Bolivarian alliance for "21st Century Socialism," led by Venezuela and Cuba.

The Latin powerhouse's acquiescence to La Paz has been particularly glaring. The trend dates to 2006, when Brasilia rolled over after the Morales government sent troops to take control of an oil refinery owned by the Brazilian oil major Petrobras. Then president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, with Rousseff as his mines and energy minister, wanly passed off the illegal seizure as "the justified" act of "a sovereign nation" that "should be respected."

Petrobras demurred, pulling out of Bolivia. Many others were outraged. "Brazil should have put its foot down and threatened to recall its ambassador to Bolivia and cancel trade agreements," says Brazil's former foreign minister Luiz Felipe Lampreia. "Brazil acts as if its hands are tied to the Morales government."

The Andean escape is likely to dominate the conversation in Latin America for now, starting with the meeting of the nations of the South American Union, Unasul, which convened Friday in Suriname. Meanwhile, all eyes will be on Rousseff's new foreign minister, Luiz Alberto Figueiredo, who takes over amid what the leading Rio daily, O Globo, called "one of the worst moments of Brazilian diplomacy."

Like The Daily Beast on Facebook and follow us on Twitter for updates all day long.

A longtime correspondent for Newsweek, Mac Margolis has traveled extensively in Brazil and Latin America. He has contributed to The Economist, The Washington Post, and The Christian Science Monitor, and is the author of The Last New World: The Conquest of the Amazon Frontier.