(above) Twilight, Uyuni Salt Flats, Potosi, Bolivia

A mirror to calibrate the senses

August 31, 2013 - TheStarPhoenix

Voyage to the amazing salt flats of Uyuni

By Dr. Ivar Mendez

(left) Dr. Ivar Mendez Photograph by: Shannon George Photography

(left) Dr. Ivar Mendez Photograph by: Shannon George Photography

Dr. Ivar Mendez was born in Bolivia and has established The Ivar Mendez International Foundation (IMIF), a charitable organization dedicated to improving the lives of children in the poorest regions of the Bolivian Andes (imif.ca). Mendez travels to Bolivia two or three times a year to oversee IMIF projects.

He visits remote communities such as the Chipayas and his trip to the salt flats of Uyuni was in conjunction with a visit to poor aboriginal communities on the shores of the salt flats.

(below) Geometry in salt, Uyuni Salt Flats

Mendez is the Fred Wigmore professor of surgery and unified chairman of the department of surgery at the University of Saskatchewan and the Saskatoon Health Region.

The rain is brief and barely a couple of centimetres of water accumulates on the surface of the ground, but the effect is utterly magic.

Suddenly, the boundary between earth and sky disappears, changing dramatically our perception of the landscape. The Toyota SUV in which we travel appears to float on a sea of cumulus clouds as if gliding over the surreal vastness of a gigantic mirror - the salt flats of Uyuni.

(below) Gliding on the sky, Uyuni Salt Flats

Ten billion tons of salt are confined to an area of 10,582 square kilometres at 3,656 metres above sea level in southeastern Bolivia, creating the largest salt flats on the planet. Calculations using a global positioning system (GPS) have shown that variations in the ground surface are less than one metre, making the surface of Uyuni the flattest region on Earth.

This surface is so uniform the salt flats are used to calibrate the altimeters of satellites orbiting the globe. The calibrations performed on the surface of the salt flats are five times more accurate than satellite calibrations that were, until recently, made using the oceans as reference. Although the annual precipitation in this region is minuscule, in the rainy season, from January to March, the salt flats are flooded by a few centimetres of water, converting it into the largest mirror on Earth, easily distinguishable from space.

We head to the interior of the salt flats where a hotel made entirely of blocks of salt has been erected. The horizon is a straight white line scratching the cobaltblue sky of the Bolivian plateau.

(below) Salt flats on fire, Uyuni Salt Flats

The hotel looks like an enlarging dot trapped between the salt and the sky as if suspended between reality and the imagination. Its blocks have a café au lait tone due to alternating layers of clay and salt.

The crust of the salt flats has 11 layers of salt with a thickness of about 10 metres. Below this superficial layer, there is a lake of brine with depths that reach 120 metres.

It contains the largest untapped reserves of lithium in the world. Lithium is in increasing demand globally as it is a key component of the manufacturing of batteries that power smartphones and electric cars. It is estimated the salt flats contain 100 million metric tons of lithium. Bolivia's prosperity in the future may depend on the salt flats of Uyuni and its reserves of lithium.

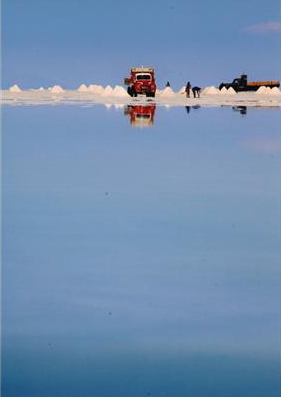

(left) Harvesting salt, Uyuni Salt Flats

(left) Harvesting salt, Uyuni Salt Flats

A native legend tells about the origin of the salt flats. In ancient times, when the mountains knew how to walk and fall in love, the stunning volcano Tunupa, who was a lovely maiden, fell in love with the mountain Kusku. Unfortunately, Kusku abandoned the pregnant Tunupa. She became very sad and while nursing her newborn her tears mixed with her breast milk and spilled on earth, forming the salt flats of Uyuni. Geologically, the salt is the product of the transformation, 40.000 years ago, of prehistoric lakes in the region.

It is late afternoon and the sun slowly sets over Uyuni, painting the sky with a palette of red, orange and gold. The sky is mirrored on the surface of the salt flats, creating a magical kaleidoscopic reflection of clouds and fire. We seem to be walking on the sky and I have an intense desire to kick a particular round cloud as if it was a football. The sun's reflection is so strong it is almost blinding.

(below) Endurance challenge, Uyuni Salt Flats

We settle in the salt hotel in the evening. The dinner is served on tables made of blocks of salt; the meal starts with a delicious soup of papalisa, which is one of the more than 5,000 varieties of potatoes that since Inca times still grow in the Andes. The main course is a tasty steak of llama meat. After dinner, we go for a walk. The night has an exquisite freshness and serenity; the pristine celestial vault is studded with the flashes of billions of stars, their prehistoric luminosity has taken light years to reach the Earth.

It dawns on me that this vast cosmic panorama so real and sublime is only the reflection of a distant past. Absorbed looking at the night sky I have not noticed that every detail of the firmament is faithfully reflected in the magic mirror of Uyuni. I can clearly see the bright expanse of the Milky Way, the Southern Cross, Orion's Belt and other constellations that seem to ride on the surface of the flooded salt flats.

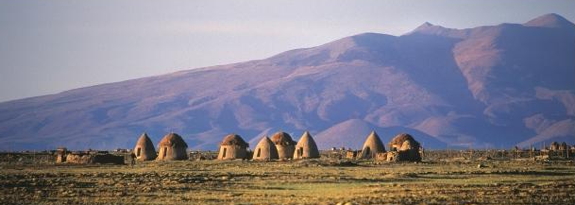

(below) Chipaya round houses, Oruro, Bolivia

It is almost a mystical experience and it is hard to resist the urge to rush to the surface of the salt flats and dive into the reflected sea of stars and constellations.

As I contemplate the cosmos displayed in stereo, simultaneously on the sky and the salt flats, my memory rewinds to the time I spent with the Chipayas, an aboriginal community located on the shores of the smaller salt flats of Coipasa about 20 kilometres north of Uyuni. I remember my admiration for their ancestral language, their culture and their round houses cleverly built to keep their interior warm by aerodynamically dispersing the icy winds that punish this region.

The Chipayas told me of the llama caravans that since time immemorial criss-crossed the salt flats of Uyuni transporting blocks of salt to the urban markets of the Inca Empire. The caravans travelled at night to avoid the blazing sun of the daytime. The llama shepherds navigated this featureless landscape by consulting the night sky, not the stars but the dark spots created by the uneven distribution of star clusters in the Milky Way. Tonight, the Milky Way is displayed at my feet in all its glory and I can clearly see in its dark spots the outline of a celestial condor with its beak pointing south. This breathtaking vision fills me with awe and I feel in harmony with myself and the universe.

(below) Chipaya women, Oruro, Bolivia