Analysis: Nervous Peruvians delay home buys before election

May 20, 2011 - Reuters

By Terry Wade and Patricia Velez

LIMA (Reuters) - Peru's topsy-turvy presidential election, already whipsawing financial markets, is now affecting the real economy as the middle-class balks at buying real estate, until now an engine of the country's boom.

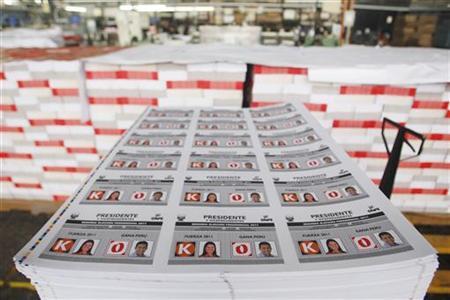

Fears left-wing Ollanta Humala will beat right-wing Keiko Fujimori in a June 5 run-off have caused buyers, lenders and builders to pause and postpone projects for the time being.

They are worried Humala, a former military officer, could roll back years of free-market reforms, despite his move toward the political center and repeated promises to respect private investment and keep existing macroeconomic policies in place if elected.

In a tight but changeable race, Humala is several points behind Fujimori, polls show. She is trusted by the business community, because her father, former President Alberto Fujimori, opened Peru's economy and tamed rampant inflation. He was later jailed for corruption and human rights abuses after his government fell in 2000.

The construction sector, driven largely by demand for new homes and easier access to mortgages, grew 17,4 percent last year, helping lift the broader economy almost 9 percent and turn Peru into one of the world's fastest-growing economies.

But in March, before the election caused a sell-off in Peru's stocks and currency, the construction sector grew just 0.15 percent from February as firms became more cautious. Broader economic growth was the slowest in 13 months.

Cement purchases, a leading indicator of the construction sector, rose just 1.25 percent in April from a year earlier.

"Everything has slowed down. I've sold one apartment since the first-round vote on April 10. Normally it'd be 4 or 5 a month. The number of people dropping by to look at projects has gone to zero," said Daniel Kohn, general manager of Inverko, a Chilean real estate development firm in Peru.

He says he is lucky that most of the 56-unit tower he is building in the fashionable Miraflores district was sold before election jitters took root and says he is being cautious about his next investment.

"I'm in negotiations right now to buy a lot to build on, but everybody involved in the deal knows that it depends on Keiko winning, and that the contract would be signed on June 6, the day after the election."

Walter Bayly, the chief executive of Credicorp (BAP.N), which owns Peru's biggest bank, Banco de Credito del Peru, has said the monthly volume of new home loans should fall in the second quarter because of election uncertainty.

"The most tangible drop is the placing of new mortgages, which is down 20 percent from last month," he said this month.

The bank now forecasts its total loan book will grow 15-18 percent this year, compared with an earlier view of 18-20 percent.

INVOKING THE CONSTITUTION

Some economists are also talking of revising downward their projections for economic growth, to about 6.5 percent from 7.5 percent. That would still be near what economists call its "potential" growth rate, where inflationary pressures are mild.

"What has been more cautious is investment, some projects have been delayed, not canceled. That means they could be reactivated after the election results are known, if the winning candidate gives the right signals to the market," Central Bank President Julio Velarde said at an event in Lima this month.

Even though there is evidence consumers are postponing home purchases, car loans surged 21 percent in April from the same month a year earlier, and nearly 1 percent from March.

Peruvian markets plunged after Humala won the first-round vote but have since partly recovered as investors bet on a Fujimori victory.

Before the latest gains, the market value of Peru's stock index .IGRA plunged by about $18 billion in less than three weeks, according to the Maximixe brokerage.

One of the reasons for selling was a proposal by Humala to take over some $30 billion in private pension funds and replace them with a government-run system. He has since abandoned the plan after strident criticism from Peru's association of private pension funds and voters.

Prima AFP, one of the country's four main pension funds, went so far as to send letters to thousands of its contributors reassuring them that their investments were safe.

"The only owner of your retirement fund is you," the letter said in bold letters. "The current constitution protects your investment."

(Reporting by Terry Wade and Patricia Velez; Editing by Andrew Hay)