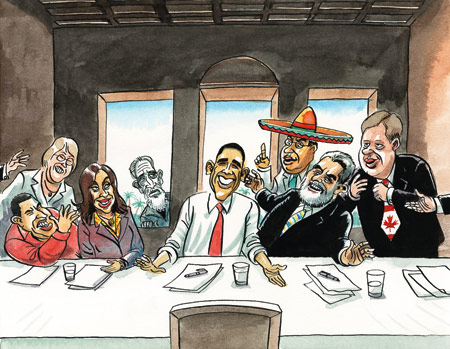

(above) Illustration by Peter Schrank

The Summit of the Americas

The ghost at the conference table

April 8, 2009 - The Economist.com

From The Economist print edition

Barack Obama will inject a new cordiality into relations with Latin America, but he will be judged on what he does on Cuba

THE last time the heads of government of the Americas got together, at the Argentine resort of Mar del Plata in November 2005, it was a fiasco. At a protest rally of 25,000 organised with the help of the hosts, Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez spent more than two hours denouncing the United States and its plans for a Free-Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA). At the meeting itself, 29 countries backed the trade plan, moribund though it was, and Mexico’s president gave Mr Chávez a public earwigging. George Bush and Brazil’s Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva left early and Argentina and Uruguay were not on speaking terms.

So the first aim of many of the 34 leaders who are due to assemble in Port of Spain, the capital of Trinidad and Tobago, between April 17th and 19th, is to preserve the diplomatic niceties and create a better atmosphere in the Americas. In this they may well succeed. For the region’s political landscape has changed. Most obviously, the United States now has in Barack Obama a president who is as widely admired in Latin America as Mr Bush was disliked. Mr Chávez is on the defensive, his socialist economy wounded as badly as any other by the world recession. The most divisive issue concerns the one country that is not invited. Latin America is now united in wanting to end the diplomatic isolation of Cuba, and many would like the United States to lift its long-standing economic embargo against the island.

That is because a transition of sorts is under way in Cuba, with Raúl Castro replacing his brother Fidel as president, even if there are no signs that this change will be matched by democracy supplanting communism. It is also because Latin America’s many left-of-centre governments, to varying degrees, see friendship with Cuba as an issue of symbolic importance.

But for the United States, Cuba is a matter of domestic politics (as are nearly all the other issues that matter to Latin Americans, such as drugs and immigration). Mr Obama was poised to announce, ahead of the summit, the scrapping of curbs imposed by Mr Bush on visits and remittances to the island by Cuban-Americans. He may also allow American companies to sell Cuba communications gear, such as an undersea fibre-optic cable, according to an administration official.

Many Americans would like him to go further. Bills introduced last month in both houses of the United States Congress with strong bipartisan support would allow all Americans to travel to Cuba. Another would ease food sales to Cuba, already allowed under cumbersome conditions. But most supporters of these bills stop short of wanting to scrap the embargo altogether while Cuba still lacks political and economic freedoms. And an influential minority in the Democratic party opposes any change in policy.

In Trinidad, many Latin Americans are likely to call for Cuba to be readmitted to the Organisation of American States (OAS), which suspended its membership in 1962. That is not straightforward, since the OAS in 2001 committed its members to embrace and defend democracy. But as Peter Hakim of the Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington think-tank, points out, the governments could ask the OAS to undertake exploratory contacts with Cuba that fall short of its formal readmission.

Whether or not Mr Obama manages to defuse the Cuba question before arriving, he will be the centre of attention in Port of Spain. Since taking office he has held bilateral meetings with Brazil’s Lula and with Canada’s Stephen Harper. He saw Mexico’s Felipe Calderón in January, and plans to visit him on his way to Trinidad. But for most of the other leaders it will be their first chance to meet Mr Obama.

Any substantive discussions will start with the financial crisis. Five of the region’s leaders were at the G-20 meeting in London earlier this month. There may be more talk of mobilising emergency funds from the IMF and regional development banks. According to Jeffrey Davidow, an experienced diplomat brought in to co-ordinate American preparations for the summit, Mr Obama will “focus on social inclusion and equity”. Those are themes that resonate with many Latin Americans.

So does co-operating on alternative energy and dealing with climate change. But this will not include any commitment from the United States to lift its tariff on Brazilian ethanol. Many Latin Americans would like to rethink the “war on drugs”, which they see as failing. Instead, there may be talk of beefing up anti-drug aid to Central America and the Caribbean, because of evidence that Mexico’s crackdown on drug gangs is driving the trade to neighbouring countries.

Caribbean leaders, many of whose economies are acutely vulnerable to the financial crisis, are requesting a separate meeting with Mr Obama. For Trinidad, the summit is a chance to promote itself as a Caribbean hub. But it is a small one: with hotels swamped, many summiteers are staying in specially-chartered cruise ships.

Administration officials insist that Mr Obama is keen “to listen” to the neighbours. Brazil stresses that the Americans should respect the political “diversity” of Latin America. Whether some of the more radical leftist leaders in the region will be conciliatory is not clear. Mr Chávez is meeting several of his allies in Venezuela prior to the summit. While saying that he wants to “reset” Venezuela’s relations with the United States, he may also try to stage a political ambush of Mr Obama.

Even if all goes more smoothly than in Mar del Plata, the balance of power in the Americas has subtly changed. Brazil has become more assertive, and its priority is to be the dominant power in South America. For Brazil, the summit is a “non-event”, says Rubens Barbosa, a former Brazilian ambassador to Washington. It sees the Summits of the Americas--the first one was called by Bill Clinton in 1994--as an American rather than a Brazilian project, indissolubly linked to the doomed FTAA.

Under Mr Calderón, Mexico wants to play a more active role in the region, but is preoccupied with drug violence and recession. Brazil and Mexico often see each other as rivals rather than allies. But the summit may confound those who exaggerate the declining clout of the United States in the region. “The summit is a one-man show. The spotlight is on Obama. Nobody else matters,” says Mr Hakim.