(above)

Illustration by Peter Schrank

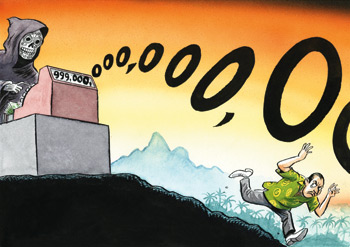

The ghost at the till

July 10, 2008 - The Economist.com

from The Economist Print Edition

Bitter experience has made Latin Americans intolerant of inflation. But have their policymakers banished this spectre?

Santiago & Sáo Paulo -- UNLIKE the developed world, Latin America has been barely touched so far by the credit crunch. Many of its economies are still growing fast, helped by demand for their commodity exports. But the commodity boom has started to have a less desirable effect: soaring food and fuel prices are pushing inflation up across the region. This has become a test of credibility for Latin America’s new-found economic stability, and for its central banks. Some of the more important ones have responded more robustly than many of their Asian peers -- even if claims that Brazil’s hawkish Central Bank is “the new Bundesbank” require a pinch of salt.

The regional average inflation rate rose to 7.5% in April, from 5.2% a year before, according to the IMF. This is an underestimate, since Argentina’s official inflation figure of 9.1% is probably less than half the true rate. It also conceals a divide. Around the turn of the decade, several of the larger countries adopted floating exchange rates, and inflation targets administered by more-or-less independent central banks. Another group of countries -- including Argentina and Venezuela -- have given greater priority to growth than to price stability. But even among the first group, inflation has been rising. In response, central banks in Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru began to raise interest rates last year. Even so, they have missed their inflation targets, in most cases for the first time (see chart below).

To howls of protest, Brazil’s Central Bank halted three years of monetary easing last October. Since then it has raised rates by a percentage point. Even so, inflation is nearing the upper limit of the target of 4.5% plus-or-minus two percentage points. Two things that have helped to contain price rises in Brazil for the past few years -- cheap goods from the rest of the world and a strengthening currency to buy them with -- have now run their course, notes Marcelo Carvalho of Morgan Stanley, an investment bank.

After initially grumbling that higher rates were making the real too strong for Brazilian industries to compete, the finance ministry is now supporting the bank’s efforts. In June it tightened fiscal policy, raising its target for the primary surplus (ie, before debt payments) from 3.8% of GDP to 4.3%. The authorities are optimistic that inflation will be falling by the end of the year. But ordinary Brazilians are alarmed by the rise in the cost of a staple basket of food -- up by as much as 50% in some parts of the country, according to DIEESE, a union-linked research body.

Brazil’s economy, along with those of Peru and Colombia, has been expanding at a faster rate than its underlying potential. But core inflation (stripping out food and fuel) has picked up in both Chile and Mexico despite sluggish growth, points out Alfredo Thorne, the chief Latin American economist at JPMorgan Chase, a bank. Mexico’s central bank is trying to steer a delicate path: it has raised rates but says that its aim is to get inflation back on target by the end of next year. With an important congressional election due next year, the government has stepped in to impose a price freeze on some staples. However, this month it raised the price of petrol.

Chile was once considered to have the best-managed Latin American economy. Its reputation has taken the biggest knock. The inflation rate has been rising for more than a year, reaching 9.5% in June. But the economy expanded by only about 3% in the first half of this year -- the lowest rate since 2002. The authorities have some excuses. Chile imports nearly all of its oil. It subsidises fuel products a bit less than some of its neighbours: the fuel subsidy (ie, the difference between domestic and world prices) is likely to amount to around $500m this year, says a Chilean official. That contrasts with $1.2 billion in Peru and $19 billion in Mexico.

Nevertheless, some economists reckon that Chile’s Central Bank has made things worse by zigzagging between worries about growth and inflation. Earlier this year it tried to halt the appreciation of the peso because of concerns this was curbing exports. Then in June it raised its benchmark rate by half a percentage point; it is expected to tighten again this week.

Given how tricky it is proving to control inflation, central bankers should probably have raised rates earlier. But finance officials could also do more to help. Fiscal spending in Latin America is very pro-cyclical, points out Santiago Levy, the chief economist at the Inter-American Development Bank. Research by the bank found that in the seven largest economies, on average governments have spent rather than saved 80% of the extra revenues they have derived from the commodity boom since 2002. Even in Chile, which saves most of the windfall, fiscal policy is expansionary, with public spending growing at double the speed of the economy.

The test will be whether or not inflation is heading down by the end of this year. If it is not, more drastic action will be required, which might make a big dent in economic growth. The wiser among the region’s politicians know that, costly though it may be, the fight against inflation is one they cannot afford to lose. Already, price rises threaten to tip several million Latin Americans back into poverty. Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, though a man of the left, has given strong backing to the Central Bank’s bitter medicine. Inflation is a “degrading disease”, he says. It is a malady that long debilitated Latin America. That is why the region is relatively intolerant of it now.